South Korea: Sex workers fighting the law and law enforcement | Reblogged from Open Democracy

Film still from Grace Period (2015). Courtesy of Caroline Key and Kim KyungMook.

By YuJin, Popho E.S. Bark-Yi, and Matthias Lehmann

South Korea introduced a raft of new laws against sex work in 2004. These repressive policies are now up for constitutional review due to the intense reaction by sex workers there.

First-time visitors to South Korea may easily assume that selling sex is legal there, as major train stations are typically engulfed by an array of neon signs inviting patrons to enter massage parlors, noraebangs (lit. a ‘singing room’, essentially the same as a Japanese karaoke bar), and brothels. Media reports frequently quote statistics about the alleged net worth of the South Korean sex industry. However, laws repressing sex work are almost as ubiquitous as commercial sex venues themselves, particularly after 2004, when South Korea adopted the anti-sex trade Laws.

Between 2000 and 2002, a series of fires in Korea killed 24 sex workers, exposing the poor conditions in parts of its sex industry. In response, the government vowed to eradicate prostitution and embarked on an aggressive campaign against businesses facilitating it. Riding the wave of public outrage, women’s rights activists campaigned for a legal reform and their proposals eventually served as blueprints for the two-tiered anti-sex trade laws, which criminalise both buyers and sellers of sexual acts, except for anyone coerced into selling sex.

The new legislation reversed decades of de facto toleration of sex work by regulators and law enforcement. The anti-sex trade laws of 2004 replaced the Law Against Morally Depraved Behaviors (prostitution) of 1961, which wasn’t enforced homogeneously, and previously, even the government had actively engaged in organising commercial sex venues to cater to US military personnel stationed on the Korean peninsula.

The anti-sex trade laws have caused many negative, allegedly unintended consequences. According to a 2012 UN report, “police crackdowns from 2004-2009 resulted in [the] arrest of approximately 28,000 sex workers, 150,000 clients, and 27,000 sex business owners”, and 65,621 arrests were reported for 2009 alone. As researcher Sook Yi Oh Kim states, “the average prosecution rate of sex workers is 26.3%, higher than that of sex buyers, and none of the sex workers arrested are treated as victims”. Police crackdowns have led to an overall reduction of red-light districts. Of 69 red-light districts that existed in 2002, 44 remained by 2013. This represented a slight increase from 2007, when a government-commissioned report had located 35.

Police raids are often carried out very violently, and in November 2014, a 24-year old single mother died after jumping out of a motel room to escape arrest by an undercover police officer posing as client. In stark contrast to their usual reporting, most Korean media remained distinctively silent about the case. The continued repression has forced an increasing number of sex workers to work underground, resulting in lower incomes, poorer working conditions, and an increase in violence perpetrated against them. Sex workers worry more about police raids than about screening their clients, an essential measure, as violence or mistreatment from clients are very common. A substantial number migrates to sell sex abroad, at times under exploitative conditions, as they calculate that conditions in Korea threaten them at least to the same extent but yield considerably lower earnings.

The trailer for Grace Period, which documents sex worker life and collective resistance in a South Korean brothel district.

Giant Girls and Hanteo against the law

Two organisations actively campaign for the rights of sex workers and against the laws. One is Hanteo, the National Union of Sex Workers, and the other is Giant Girls. Hanteo, which means ‘common ground’, was founded in 2004 and represents 15,000 sex workers as well as some brothel owners. Giant Girls, or GG, was founded in 2009 by a group of feminists along with a number of sex worker activists. GG aims at building a stronger sex worker movement to mobilise against the criminalisation of sex work, in part by working to remove the social stigma attached to sex work.

Yujin started selling sex online five years ago, in order to afford his tuition fees. YuJin self-identifies as a gay sex worker and is a member of GG. Prior to his entrance into the business he had never met anybody who was ‘out’ as a sex worker, and he knew nothing about how to work. Since all aspects of sex work are illegal in Korea, beginners often feel isolated and lack basic work and safety information. Yujin decided to tweet about his experience soon after he started working, which brought him into contact with other sex workers. Like him, these other sex workers did not ‘act immorally to earn easy money’, as the prejudice would have it, but worked hard, albeit without being respected as workers and citizens.

In 2005, sex workers established 29 June as the national day of solidarity with sex workers, coinciding with the date on which the laws were passed. Resistance from sex workers has taken many other forms. Protests organised by Hanteo in 2011 gained worldwide notoriety, as they culminated in dramatic scenes at the Yeondeungpo red-light district in Seoul, where some activists threatened to self-immolate as the confrontation with the police escalated. The events are well documented in the film Grace Period by Caroline Key and KyoungMook Kim.

In 2013, District Court Judge Won Chan Oh submitted a request for a constitutional review of the laws after accepting the argument made by sex worker Jeong Mi Kim that sex work fell under her right to self-determination. Therefore, in sentencing her for selling sex the state had violated article 10 of the Korean constitution, which holds that “all citizens shall be assured of their human worth and dignity and shall have the right to pursue happiness”.

This opened a window for a phase of much more intense sex worker activism. In April 2015, sex workers and activists staged a protest in front of the constitutional court where a public hearing was held as part of the review. They submitted a petition signed by nearly 900 sex workers arguing that the government had no right to “use criminal punishment to discourage voluntary sex among adults”. The following June, GG organised a forum to draw further attention to the fact that “these laws are not simply laws that aim to punish buyers and sellers of sexual services, but have far wider implications … encompass[ing] social issues including sexual morality, sexual self-determination, and the right to choose one’s vocation”.

Sex worker activist Yeoni Kim once said in an interview with Matthias (one of the present authors) that, “the Swedish model is terrible, violates sex workers’ rights, and adds to the stigmatisation of sex work. But, frankly speaking, one could almost say it would be better to have that terrible law than having to continue fearing arrests and police violence under the anti-sex trade laws.” Hearing one of the most seasoned Korean sex worker activists prefer a slightly less terrible law over another should put all talk about ‘choice’ and ‘agency’ into perspective.

In September 2015, Hanteo staged a larger protest in downtown Seoul. Around 1,500 sex workers demanded an end to the government’s repression, shouting slogans and holding up signs in Korean and English that read “Repeal the anti-sex trade laws!”, “we are workers!” or “adopt Amnesty’s declaration!”.

Last year, when the constitutional court struck down the 62-year-old adultery law, it cited “the country’s changing sexual mores and a growing emphasis on individual rights”. Similar logic should govern the decision on the anti-sex trade laws, which is still pending, however some women’s rights and social conservative groups are continuing to stage protests to prevent a decision against the laws, citing fears over human trafficking and minors engaging in sex work.

Migration from Asian countries to South Korea has increased in recent years, and nobody suggests that the country is immune to migrant smuggling or human trafficking. Marriages between comparatively affluent Korean men and poorer southeast Asian women remain common in rural areas, as do the problems arising from illegal practices by marriage brokers or from violence perpetrated by Korean men against their foreign wives, whom they sometimes appear to seek only for reproductive purposes and household or farm labour.

There have also been occurrences of migrants being trafficked into commercial sex venues, but it is crucial to separate human trafficking from consensual adult sex work. Cases of human trafficking or exploitation of migrants have been detected in numerous industries, including in the fishing, agricultural, or manufacturing industries. Migrants of all genders, as well as Korean citizens, are affected by conditions amounting to forced labour. It is therefore disingenuous to suggest that the problem is limited to women who are forced to sell sex, and to thereby disregard the experiences of trafficked persons and migrants in other industries, which include sexualised violence.

We are opposed to any form of violence. Sex and sexualised violence, however, are not the same. Consensual sadomasochistic sexual practices and actual violence are different, just as consensual sex work and being trafficked into the sex industry are different. People may choose to engage in sex work because they experience stigma as single mothers or due to their sexual orientation, or if other factors limit their options on the formal labour market.

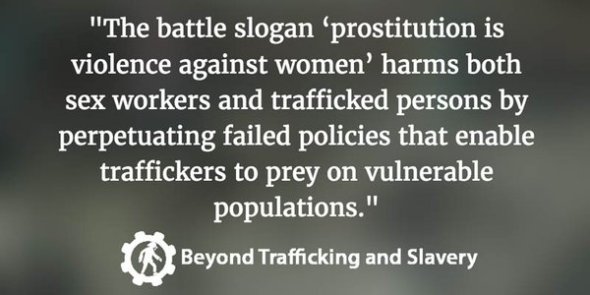

Sex work itself is not violence and to suggest otherwise dilutes the meaning of violence. If we really want to curb human trafficking, we have to address the systemic circumstances that marginalise people and render them vulnerable. As sex workers’ rights activists, we have a stake in seeing human trafficking effectively addressed. The battle slogan ‘prostitution is violence against women’ harms both sex workers and trafficked persons as it drives the creation and perpetuation of precisely those failed laws and policies that enable traffickers to prey on vulnerable populations.

About the authors

YuJin self-identifies as a gay sex worker and is a member of Giant Girls, one of two organisations actively campaigning for the rights of sex workers in South Korea.

Popho E.S. Bark-Yi is a feminist researcher and activist in South Korea. Her work focuses on sexuality and on basic income.

Matthias Lehmann is a German researcher and activist, currently focusing on sex work regulations in Germany. His prior research dealt with human rights violations against sex workers in South Korea. He is an active member of ICRSE.

This article was first published by Open Democracy as part of the ‘Sex workers speak: who listens?’ series on Beyond Trafficking and Slavery, generously sponsored by COST Action IS1209 ‘Comparing European Prostitution Policies: Understanding Scales and Cultures of Governance’ (ProsPol). ProsPol is funded by COST. The University of Essex is its Grant Holder Institution. Please note: this article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact Open Democracy. Please check individual images for licensing details.

“It ain’t what they call you, it’s what you answer to.” – or: Putting SWERFs’ abuse to better use

Sex work stigma

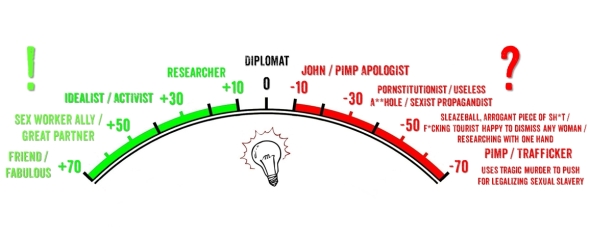

If you read any of the articles published in the days before and after Amnesty International’s decision to support decriminalising sex work, e.g. this one by Luca Stevenson and Agata Dziuban, you are now hopefully aware of the immense stigma sex workers are faced with in their everyday lives, affecting not only them but also their families and friends. To a much lesser degree, the stigma can also affect sex workers’ clients, although at worst, they might be faced with ridicule or ostracism, not violent attacks. However, the stigma might well play a role in why clients are rarely seen sacrificing their anonymity to stand up for the rights of sex workers whose services they enjoy. As a researcher, I don’t feel any tangible impact by the stigma attached to sex work research, but I certainly experience my fair share of verbal abuse. Following the Twitter battle before and after Amnesty’s decision, I’ve updated the above peak meter, which I created a couple of years ago, to include the latest labels others have attached to or hurled at me.

This blog post may appear somewhat self-referential but I would actually like to use the labels, good and bad, as vehicles to point readers to several interesting articles, some of which were written by sex workers, others by researchers, not that the two are mutually exclusive, and yet again others by sex worker-exclusionary radical feminists (SWERFs). Please note that the below is by no means intended to compare my experience to the stigma and its consequences faced by sex workers.

Red Labels

[-10] John / Pimp Apologist

Trying to shame sex workers or sex workers’ rights advocates by labelling them “johns” is very common, although it doesn’t really make much sense. After all, if someone believes that consenting adults should be allowed to buy and sell sexual services, being called a “john”, although buying sex carries its own stigma, is pretty much the same as being called a customer, which is hardly an insult.

Click image to read a report by Chris Atchison about sex buyers in Canada

Click image to read a report by Chris Atchison about sex buyers in Canada

A prostitution prohibitionist using the pseudonym Stella Marr once called me a “pimp apologist” before later deleting her comment. Although she set her own blog to “private” after she was outed, you can still read her libellous article “Pimps Posing as Sex Worker Activists” at the “Anti-Porn Feminists”-blog, in which she slanders veteran sex worker activists Maxine Doogan, Norma Jean Almodovar and the late Robyn Few, founders of the Erotic Service Provider Legal, Educational and Research Project (ESPLER), the International Sex Worker Foundation for Art, Culture and Education (ISWFACE), and the Sex Workers Outreach Project USA (SWOP-USA) respectively.

[-30] Pornstitutionist / Useless A**hole / Sexist Propagandist

Francois Tremblay, in his own words a “pessimistic feminazi, radical whackjob and antinatalist”, responded to a blog post of mine with one of his own, in which he labelled me a “pornstitutionist”, a term, as he explained, “for people who oppose abolitionism in prostitution and pornography”. His post “The strange connection between pornstitutionists and lying” is still online. He later added a postscript with the above mentioned expletive.

After I had posted a series of memes to mock the Hollywood celebrities who had gullibly believed the false claims by the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW) and co-signed a letter to oppose Amnesty‘s draft policy, a self-declared radical feminist tweeted that my memes were “sexist propaganda” and that I should quit insulting women’s intelligence – although my post includes memes mocking male celebrities, too. I wouldn’t usually mock spelling mistakes, but, well…

[-50] Sleazeball etc.

All of these are comments left about me underneath a post at the “Anti-Porn Feminists”-blog. To get an idea about the barrage of abuse that sex workers are regularly faced with, please read the Storify entry #whenantisattack, gathered by a group of current and former sex workers to highlight the silencing, shaming, abuse and insults by those who oppose sex work.

[-70] Pimp / Trafficker

In 2013, an Irish-based tabloid re-posted a video that YouTube had previously removed since it violated its terms and conditions. In the video, an undercover reporter of the tabloid filmed and outed a sex worker without her consent. In the comment thread underneath the video, a troll called me both a pimp and a trafficker. While that video was a particularly extreme example, media reports regularly add to the stigma attached to sex work, which is why in December 2014, four South African organisations jointly published “A guide to respectful reporting and writing on sex work”. An article about the guide was published in Open Democracy‘s excellent series Beyond Trafficking and Slavery. To download the complete guide as PDF please click here.

While that video was a particularly extreme example, media reports regularly add to the stigma attached to sex work, which is why in December 2014, four South African organisations jointly published “A guide to respectful reporting and writing on sex work”. An article about the guide was published in Open Democracy‘s excellent series Beyond Trafficking and Slavery. To download the complete guide as PDF please click here.

https://twitter.com/CharoShane/status/443372896338313217

The term “pimp lobby” is frequently used by sex worker-exclusionary radical feminists (SWERFs) to slander “anyone who advocates anything but the full criminalization of sex work”. Apart from watching the video below, I recommend reading “Hanging out in the Pimp Lobby” by Jemima, “Everything You Need To Know About The Pimp Lobby” by Charlotte Shane, and “I Am the Pimp Lobby” by Jes Richardson.

Perhaps the worst insult I’ve experienced was one during the Amnesty #ICM2015 twitter battle, when a Canadian anti-prostitution activist accused me of using the murder of Swedish sex worker activist Petite Jasmine to further my alleged agenda to legalise “sexual slavery”.

Black + Green Labels

[0] Diplomat

A French sex worker activist once told me I wrote even “more politely than English people”. I believe that any movement needs different types of activism and writing. Some of it needs to be fierce; at other times, it’s better to be diplomatic. I’m always up for creating satirical memes, but in my writing, I prefer to be very diplomatic, although when faced with ideologues like Rhoda Grant or Mary Honeyball, that’s not always possible.

[+10] Researcher

[+30] Idealist / Activist

What an American and a Turkish friend in South Korea called me. Justice Himel from the Ontario Court of Justice found that anti-prostitution activist Melissa Farley had allowed her advocacy to permeate her opinions. Although Farley’s work has been frequently discredited, anti-prostitution activists continue to cite her in support of sweeping claims about sex work, just as the notorious Cho/Dreher/Neumayer study is constantly rolled out to back up the argument that legalising sex work leads to greater human trafficking inflows, despite the seriously flawed data used to make that argument. I believe on both sides of the divide, it’s sometimes difficult to remain detached when people close to oneself experience violent abuse. When it comes to activism for the rights of sex workers, I believe it’s important to acknowledge what you don’t know and stay clear of problematic arguments. And that’s true regardless of whether you are a sex worker, a researcher, a journalist, an artist, a writer, or any combination of these.

[+50] Sex Worker Ally / Great Partner

What sex workers have called me. Recommended reading on the subject: How to be an ally to sex workers by SWOP Chicago + Want to be a hero for sex workers? Try listening by Tilly Lawless.

[+70] Fabulous / Friend

What the above mentioned French and a South Korean sex worker activist have called me.

Epilogue

My preferred way of dealing with SWERF attacks is to create memes and share them with the #sexwork community or respond with counter evidence to the most ludicrous claims, like the one about sex workers’ rights advocates allegedly living in a land of milk and honey, when actually, it’s faux anti-trafficking organisations who rake in the dough.

Should you experience verbal abuse because you publicly stated your support for policies to safeguard sex workers’ human rights, try not to let it get to you. As American comedian W.C. Fields once put it, “it ain’t what they call you, it’s what you answer to”.

Celebrating Hollywood’s “gender studies scholars”

Images* to celebrate Hollywood’s “gender studies scholars” who, after conducting “some very scientific studies”, have co-signed a letter by anti-prostitution activists to try and pressure Amnesty International into dropping plans to adopt a policy that would recommend decriminalising sex work.

Tell Amnesty to listen to sex workers!

Please read, sign and share the petition by the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) and tell Amnesty to listen to sex workers and protect their human rights!

Recommended Reading

Sarah (Tits and Sass)

A Tale of Two Petitions: CATW’s Amnesty Open Letter Fail

Luca Stevenson and Agata Dziuban (ICRSE)

Amnesty must stand firm on support for decriminalising sex work

Caty Simon (Tits and sass)

Pye Jakobsson (NSWP President) on the Amnesty International vote and holding allies accountable

Michel Sidibé (UNAIDS Executive Director)

UNAIDS Letter of Support to Amnesty International [PDF]

Sebastian Kohn (Open Society Foundations)

Why Amnesty International Must Hold Firm in Its Support for Sex Workers

Wendy Lyon (Feminist Ire)

On Amnesty and that open letter

Thomas Schultz-Jagow (Amnesty Int’l)

Response to Jessica Neuwirth’s article in the New York Times

Amnesty International

Explaining our draft policy on sex work

Kathryn Adams

18 Reasons for Decriminalisation of Sex Work

(Adapted from Amnesty International’s Draft Policy on Sex Work)

Chantawipa Apisuk (Empower Foundation Thailand)

Letter of Support to Amnesty International

Kay Thi Win (Asia Pacific Network of Sex Worker)

Please vote Yes to the policy on decriminalization of sex work

Juniper Fitzgerald (Tits and Sass)

Celebrity And The Spectacle Of The Trafficking Victim

Alison Phipps (Director, Gender Studies, University of Sussex)

‘Disappearing’ sex workers in the Amnesty International debate

James Baer (London); Barbra Moyo (Sexual Rights Centre, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe)

Guardian Letters: Amnesty International is right to take a stand on sex work

Molly Smith

In this prostitution debate, listen to sex workers not Hollywood stars

Serra Sippel (President, Center for Health and Gender Equity)

All Women, All Rights – Sex Workers Included

Rachel Vorona Cote

Celebrities Have Vital Opinions About Decriminalization of Sex Work

Jamie Peck

Sex workers tell Lena Dunham, other celebs to STFU about shit they don’t understand

…or check out #Amnesty4Sexwork on Twitter.

*All images modified by Research Project Korea/Germany (@photogroffee). Feel free to share and retweet. See image descriptions on Facebook for Twitter URLs.

The Anti-Sex Trade Laws – are they unconstitutional?

2015 Panel Discussion commemorating Sex Workers’ Day

“On April 9th, 2015, a public hearing was held at South Korea’s constitutional court regarding the constitutionality of the Anti-Sex Trade Laws. These laws are not simply laws that aim to punish buyers and sellers of sexual services, but have far wider implications. The laws encompass social issues including sexual morality, sexual self-determination, and the right to choose one’s vocation. In this light, Giant Girls Network for Sex Workers’ Rights will hold a panel discussion to review the aforementioned public hearing. The event will be held on Sunday, June 28th, 2015. Thank you for your interest and participation.”

“2015년 4월 9일 성매매특별법 위헌제청 공개변론이 열렸습니다. 성특법은 단순히 성구매자와 판매자의 처벌에 관한 법률이 아닙니다. 이 법에는 우리 사회의 성도덕, 성적 자기결정권의 국가 개입, 직업선택권 등의 복잡한 문제가 얽혀 있습니다. 성노동자권리모임 지지는 이 공개변론이 성특법에 대한 논의에서 중요한 역할을 했음에도 불구하고 공론화 되지 못함을 안타깝게 생각하여 6월 28일 일요일 공개간담회를 열고자 합니다. 많은 분들의 관심과 참여를 부탁드립니다.”

Event Details

Chair: Sa Misook 사미숙 (Giant Girls)

Panellists:

Jeong Gwan Yeong 정관영 (Attorney)

Prof. Park Gyeong Shin 박경신 (Korea University, argues that the laws are unconstitutional)

Prof. Oh Gyeong Sik 오경식 (Kangrengwonju University, argues the laws are constitutional)

Jang Sehee 장세희 (Vice President, Hanteo National Union of Sex Workers)

Prof. Go Jeong Gaphee 고정갑희 (Hansin University)

Kim Yeoni 김연희 (Sexworker/Activist)

Date/Time: June 28, 2015 Sunday 13:30~15:30

Address: Bunker 1, Seoul Jongno-gu Dongsung-dong No 199-17 Floor -1 Danzzi Ilbo

서울특별시 종로구 동숭동 199-17번지 지하1층 딴지일보

Organiser: Giant Girls Network for Sex Workers’ Rights 성노동자권리모임 지지

Contact: Oh Gyeong Mi 오경미 010-4812-3350

Entrance is free. This event will be held in Korean.

Further Information

Anyone unfamiliar with the ongoing constitutional review of South Korea’s Anti-Sex Trade Laws might find it helpful to read Choe Sang-Hun’s recent summary in the New York Times. Please note that this recommendation does not represent an endorsement of the terminology used therein.

June 29th ☂ Korean Sex Workers’ Day

On this day, the National Solidarity of Sex Workers Day was organised, after the Special Anti-Sex Trade Law [which includes a Prevention Act and a Punishment Act] was passed in 2004. Since then, the date is commemorated as Korean Sex Workers Day to honour all sex workers who have contributed to the struggle against discrimination over the years.

“Red Light Research” – Interview by Malte Kollenberg

Sex workers and allies protest in front of the South Korean Constitutional Court.

© 2015 Research Project Korea. All Rights Reserved.

Summary

In May, I accepted an interview request by Malte Kollenberg, a freelance journalist producing a series about Germans living in South Korea for KBS World Radio. After several negative experiences with the Korean media, it was refreshing to meet a sincere journalist willing to go the extra mile to communicate before, during and after our encounter to ensure that the subject of sex work would be dealt with appropriately.

Listen to the interview in German or read the translated transcript below.

Please note that the copyright for the interview recording lies with KBS World Radio and is not licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Interview

Introduction by Malte Kollenberg

Matthias Lehmann’s research deals with a stigmatised occupation. He currently works on his dissertation about sex work regulations in Germany at Queen’s University Belfast. Over the last years, he’s created his own niche. Starting from his interest in North and South Korea, and later in human trafficking prevention in Thailand, he presented in 2013 the results of a privately funded research project about the impact of the South Korean Anti-Sex Trade Laws on sex workers’ human rights. And South Korea is still on his mind. Lehmann actively engages for improved working conditions for sex workers. For the “Meeting of Two Worlds”, we’ve met Lehmann in Busan and spoke with him about his research, the differences between Germany and South Korea, and his critique of the media.

Malte Kollenberg: Mr Lehmann, what brought you to South Korea?

Matthias Lehmann: I first came to Korea was in 2002. I majored in Korean Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, and the first time I came here was as a visitor, and then I returned later as an exchange student. Back in Berlin, my home town, I had quite a few Korean friends, and that’s how I came in contact with Korean culture, especially with Korean music, and of course with Korean films. My family’s history was shaped by the German division. I was born and grew up in West Berlin, but I also had relatives in East Berlin and other, smaller cities, all the way down to Saxony, and often visited the former GDR. That’s why the history of the Korean division is both a very interesting and emotional issue for me, and that was one of main reasons why I got into the field of Korean Studies.

MK: In the meantime, your research field is an entirely different one, however, and has little to do with the Korean division.

ML: Right. During my previous studies, and also for some time after that, I was particularly interested in North Korea and the role of the United States in the so-called North Korean nuclear crisis. Afterwards, I first shifted my focus onto the field of human trafficking. I did my master’s degree here in Korea and the subject I then wanted to focus on, sex workers’ rights and prostitution laws, which is the subject I am also dealing with now, I couldn’t get approved by the faculty at my university here, and I guess I can understand that. That was why I continued to focus on human trafficking prevention for my M.A. thesis, but of course that included illustrating how laws that should actually fight human trafficking, like here in Korea, negatively affect the rights of sex workers, especially of migrant sex workers. So, that’s how my research interest developed: first Korea, then human trafficking, then sex work. And although I first focused on Thailand, I later returned to South Korea to focus more closely on the situation here after the huge protests in Seoul in 2011.

MK: You also did research about this subject from a German perspective. Generally speaking, are there great differences between how sex work/prostitution is regulated by law in Germany and South Korea?

ML: Yes, there’s a huge difference. I’ve now begun to focus on Germany for my doctoral degree, and it’s exciting for me to do research about my own country for the first time. In Germany, sex work has been legal for a very long time. The media often report that Germany legalised prostitution in 2002 but that is actually incorrect. Prostitution was already legal for most of the 20th century, with the exception of the Nazi period. What changed in 2002 was that a law was created to strengthen the legal and social rights of sex workers, and that the operating of brothels was permitted. That’s what changed. But sex work was already legal, both the buying and the selling of sexual services.

And that’s exactly what is prohibited in Korea, which means that brothel operators, people who facilitate contacts, for example escort agencies, and also sex workers themselves are all prosecuted here. And it does happen! I’ve often experienced that both Koreans and foreigners living in Korea say that they believe nothing is being done and that the police is always looking the other way. And that really isn’t true. It might only be a drop in the bucket – but that drop hits the target. In fact, there are many raids here, and since last year, they’ve actually increased again. People are arrested and sentenced, people have to appear before the court, and last November, a woman even died as a result of a raid, because she panicked and jumped out of a window to escape the police.

That was a very interesting case and that’s where we come to the media. If any “prostitution ring” or human trafficking case is uncovered in Korea or abroad, where Korean sex workers are involved, or victims of human trafficking, which of course can also occur, then the Korean media always report about it immediately and extensively in their English editions and on their English websites, because that’s “sexy” news. But when that woman died last November – absolute silence! Nobody wanted to report in English that this sort of thing also happens. Of course there were some reports about it in Korean, but they were not good and very disrespectful. In one of them, there was a cartoon that showed two police men looking down from a tall building and a dead woman lying below. How one can even have such an idea is a mystery to me. Of course there isn’t always such extreme harm involved, but raids do happen and the human rights of sex workers here in Korea are being violated. That’s a big problem.

MK: You just said that the media are keen on such “sexy” news. And that’s exactly how it is. Sex always sells in the media. You must be flooded with media requests.

ML: Indeed. With the exception of September 11, I’ve never experienced such an avalanche of media reports as in the last 18 months, both in Germany, but also in the UK. In Germany, that’s because there’s an ongoing discussion about changing the prostitution law. There’s a new bill but it has already been in the works for quite a while and no final decision has yet been made. The ruling coalition will probably just push it through parliament since they have such great majority there. In Northern Ireland, Scotland and also in the British House of Commons, different attempts were made to introduce laws to criminalise the purchase of sexual services. [In Northern Ireland, a law criminalising sex workers’ clients has come into force on June 1st, 2015.] And in Korea, there are also a lot of media reports, especially due to the ongoing constitutional review concerning the Korean anti-prostitution law.

MK: What might be the outcome of that?

ML: I didn’t really look very deeply into the adultery law, which was recently changed here so that adultery is now no longer punishable by law, but in the wake of that decision, it is of course possible that the constitutional judges, they’re eight men and one woman, will take the next step and say that the prostitution law also needs changing. But I don’t quite believe it yet. There have been constitutional reviews of the law in the past, but those weren’t submitted by a judge. However, two years ago, a Korean sex worker stood before the courts because she had sold sex, and she insisted on her right of self-determination, which resulted in the presiding judge at the Seoul Northern District Court submitting a request for a new constitutional review of the law.

The review should have been concluded already, but these things take a lot of time. In the case of the adultery law, for example, it took four years. The first public hearing was in April and the process will continue. The experts I’ve heard giving evidence so far represent a mixed bag. Sex workers are not sufficiently included. It’s bad enough in Germany, but here, it’s even worse. Although there are two different sex workers’ rights organisations, sex workers haven’t presented evidence so far. Instead, that was done by lawyers, researchers, and other experts, so that at the hearing, sex workers themselves weren’t heard. At least in Germany, even if that was merely a fig leaf, we did have a sex worker presenting evidence in front of the justice committee of the German parliament. But here, nothing of that sort happened.

MK: Let’s return to the media. On your blog, you published a media critique some time ago. What problems do you see when it comes to media reports about prostitution/sex work?

ML: Well, it wasn’t just one media critique but sadly, it’s a recurring issue, and it’s always a lot of work. I only focus on those that matter, for example, if there’s a detailed report from the BBC or from [German broadcaster] ARD. When it comes to reports about Korea, then what you mostly see in the German media are the latest stories to have allegedly happened in North Korea, and those stories are often trumpeted before they’re even confirmed, simply because they make for good clickbait. And when it comes to prostitution, there is no value set on fact-checking or actually speaking to members of the occupational group concerned. When the train drivers or pilots in Germany go on strike, then journalists speak with representatives of those occupational groups. Sadly, when it comes to sex work, that just doesn’t happen. Or if it happens, then they are harassed to make certain statements they don’t want to make, or do certain things they don’t want to do. I remember talking with a sex worker while I was doing my research project here in Korea, who told me that after the 2011 protests in Yeongdeungpo, that’s a red-light district in Seoul, one of the media teams insisted on filming her while she would do the dishes at a brothel. She replied to them that she never does that, so why should she do it now? Their idea was obviously to convey a message like, “Look, sex workers are normal people, just like you, doing normal things.” Maybe from a very naïve perspective, one can understand their motivation, but it’s still nonsense to try and fabricate something like that. Instead of trying to put words into their mouths, shouldn’t they actually report about what sex workers’ concerns and demands are?

On July 19th, 2013, people gathered in 36 cities across the globe

to protest against violence against sex workers. | Official Website

MK: The topic sex work/prostitution is so complex. Is there anything that you would like to add that you consider as particularly important?

ML: Yes, thank you. Ever since the global protest in June 2013, after two sex workers were murdered in Sweden and Turkey, the #StigmaKills hashtag is being used on Twitter. It refers to the fact that the stigmatisation of sex work and of sex workers really does result in deaths – or at the very least, it has a very negative impact on sex workers. Something I notice time and time again, especially here in Korea, is that people either feel sorry for sex workers, which they really don’t need, or they’re angry about them, which happens both in Korea or in the Korean communities in Australia, for example. They are angry because they seem to think that Korean sex workers who work abroad are giving Korea a bad image. But the reason why many Korean sex workers have migrated to work abroad is that the law, which was adopted here in 2004, criminalises them, and that the risks they’re taking by working abroad, for example in the US where sex work is also illegal, are still more predictable, or the conditions more attractive, than the risks they’d face if they were to stay and work here. People should finally listen to sex workers, and not just let off steam based on their prejudices.

MK: Thank you very much, Mr Lehmann.

ML: You’re welcome.

Please note that the copyright for the interview recording lies with KBS World Radio and is not licenced under a Creative Commons License.

Interview by Malte Kollenberg. © 2015 KBS World Radio. Translation by Matthias Lehmann. The English version differs slightly from the German original to make for easier reading. I would like to thank Malte Kollenberg for his professional attitude and sensitivity throughout our communication before, during and after the interview.

Related Posts

Articles tagged “Media Critique” on Research Project Korea

A fair deal? – South Korean sex workers’ earnings at home and abroad

In Pictures: Sex workers protest in front of South Korea’s Constitutional Court

Lies & Truths about the German Prostitution Act – An Introduction for the Uninitiated

Distorting MIRROR: The media’s fear of the truth [SPIEGEL Critique]

Does legal prostitution really increase human trafficking in Germany? [SPIEGEL Critique]

[Video in German] “Sex Crime” or “Sexual Self-Determination”? Prostitution discourses in South Korea

Re-blogged: Will South Korea’s queer movement embrace or abandon MTF transgender sex workers?

Lucien Lee at the 2014 Korea Queer Festival in Seoul.

Photo © KQCF (left) and © Lucian Lee (right). All Rights Reserved.

By transgender sex worker Lucien Lee in Seoul

한국어 원본을 보시려면 여기를 누르세요.

Please note that the different copyrights for the respective photos.

Homosexuals once used to be outlaws, persecuted by the police and at the mercy of powerful justice systems in countries we now refer to as advanced. However, many places remain where homosexuals continue to be persecuted and even killed. In South Korea, however, homosexuals have never been outlaws. Unless a homosexual male engages in sexual activities with another person of the same gender while on leave from his mandatory military service, in which case the infamous Article 92 (6) of the Military Criminal Code, also known as “Sodomy Law”, applies, South Korea does not outlaw homosexuality. [1]

That may have been the reason why South Korea’s queer community had great difficulties to accept it when sex workers, who are criminals according to the 2004 Anti-Sex Trade Laws, joined the 2013 Korean Queer Festival and identified themselves as sexual minorities oppressed by sexual morality. Comments like “What are you whores doing here?” came as no surprise because nobody would want to mingle with outlaws.

When I joined the Korea Queer Festival a year later as a transgender sex worker together with other sex workers, the reactions from people were quite different. Maybe that was because they couldn’t easily other me as a non-queer “whore” because I am a male to female transgender person. That day, we handed out a thousand copies of “A letter from independent sex worker ‘T’ to the LGBAIQ community”. [2] But other than that, sex workers’ rights are still not considered a part of queer issues.

Various research reports provide data about the ratio of sex workers among transgender people but those figures vary widely due to their limited sample sizes. It is undeniable, however, that those working at Itaewon’s transgender bars are the most visible group of South Korea’s transgender community.

On May 23rd, 2015, South Korean daily Dong-a Ilbo featured an article about transgender sex workers, which revealed the particular locations, times, and how much money is required to buy sexual services. But even before that article, it was impossible to hide transgender sex workers from the public view, and this visibility, together with a greater awareness among the cis-straight society in general, will likely result in police raids specifically targeting transgender sex workers, just as they targeted and demolished red light districts before.

A taxi driver interviewed for the abovementioned article said, “I’ve been a taxi driver for almost twenty years, and they [transgender sex workers] were already here when I started.” Traditionally, sex work is often the only viable source of income for male-to-female transgender people. We cannot survive economically if such a transgender-specific persecution occurs. We cannot easily change our jobs.

Sex workers and activists protest in front of South Korea’s Constitutional Court.

© 2015 Matt Lemon Photography. All Rights Reserved.

On April 9th, 2015, a first public hearing was held at South Korea’s constitutional court in the ongoing review to determine whether the 2004 Anti-Sex Trade Laws are unconstitutional. Article 21 (1) of the Anti-Sex Trade Laws Punishment Act penalises sellers of sexual acts with up to one year in prison or fines of up to 3 million won (approx. £1,765/€2,485/$2,735), except for those who were coerced. The article is not gender-specific and therefore applies to male and transgender sex workers, too.

The female sex worker, whose arrest and subsequent trial led to the constitutional review, standing in the middle of the above photo, argues in favour of the decriminalisation of sex work limited to female sex workers only. However, members of South Korean feminist organisations, who used to advocate for what they referred to as “decriminalising female prostitutes”, have spoken out against this woman as they fear that if the article were to be ruled unconstitutional, buying sexual acts would also no longer be criminalised. Even if one were to accept their opinion that female sex workers are victims of a capitalist system, and hence innocent, whereas male buyers are guilty, their insistence on keeping the 2004 Anti-Sex Trade Laws makes no sense, as it punishes innocent people.

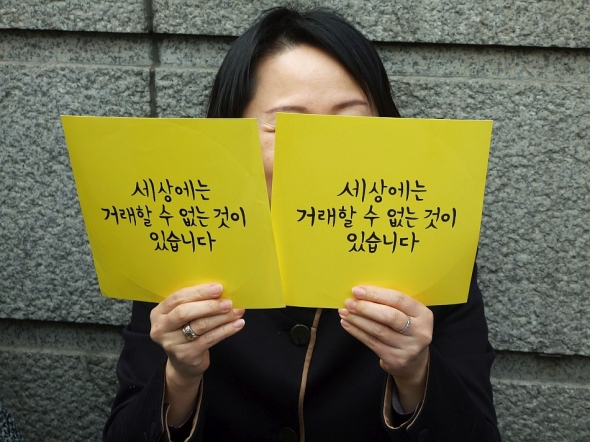

Anti-prostitution activist holding up signs saying

“There are things in the world that cannot be traded.”

© 2015 Matt Lemon Photography. All Rights Reserved.

Despite the importance of this review, none of the LGBT organisations has so far made their stance on this issue publicly known. That is one of the reasons why, although the sexual minority movement is often referred to as “LGBT” or “queer” movement, in reality, it is more considered as a “homosexual” movement by the public.

Police raids targeting transgender sex workers would force transgender people to organise demonstrations in the same way as sex workers working at the Yeongdeungpo red light district did to protect their right to survive. If such protests were to happen, I wonder what stance LGBT organisations would take. Would they abandon transgender sex workers or stand together with them? Let us all take this very seriously and think about it together. See you all at the 2015 Korea Queer Festival.

Footnotes

[1] While engaging in sexual activities on military premises is generally forbidden, Article 92 (6) of the Military Penal Code states that “anal intercourse or other harassment against any person … shall be punished by imprisonment of up to two years” even if it occurs while on leave. LGBT rights’ activists argue that this paragraph is used to single out sexual relations between members of the same sex.

[2] A small clarification for readers less familiar with the acronyms: LGBTAIQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, asexual, intersex, and queer, and the T was here purposefully left out as ‘T’ addressed the LGBAIQ community.

Translation by Lucien Lee. Edited by Matthias Lehmann. I would like to thank Lucien Lee for her permission to reblog this article. The English version differs slightly from the Korean original and features two different photos. Footnotes were added for further clarification.

In Pictures: Sex workers protest in front of South Korea’s Constitutional Court

Photos taken on April 9th, 2015, as sex workers and activists gathered in front of South Korea’s Constitutional Court in Seoul ahead of a public hearing, part of the ongoing review of the country’s Anti-Sex Trade Laws. The sex workers depicted in these photos consented to them being published online. All photos © 2015 Matt Lemon Photography. All Rights Reserved.

Photos taken on April 9th, 2015, as sex workers and activists gathered in front of South Korea’s Constitutional Court in Seoul ahead of a public hearing, part of the ongoing review of the country’s Anti-Sex Trade Laws. The sex workers depicted in these photos consented to them being published online. All photos © 2015 Matt Lemon Photography. All Rights Reserved.

+++ Update Sept. 23rd, 2015 | Please read E. Tammy Kim’s article for Al Jazeera America, titled Korean sex workers demand decriminalization of their labor +++

Open Letter to the Modern Slavery Bill Committee

Palace of Westminster, London (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Palace of Westminster, London (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In response to a call by the English Collective of Prostitutes, I sent the following letter to the chair and all members of the Modern Slavery Bill Committee at the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.

+++ SEE UPDATE BELOW +++

Dear Mr Field, Dear Mr McDonnell,

and Dear Members of the Joint Committee on the Draft Modern Slavery Bill,

Without a doubt, you will receive plenty of emails containing objections to clauses of the Modern Slavery Bill, and I’m afraid this is another one. I am a German doctoral researcher at Queen’s University Belfast, where my focus lies on prostitution regulation in my native Germany. Over the last years, I have conducted research into measures to prevent human trafficking in the Mekong Sub-region and human rights abuses against sex workers in South Korea, resulting from Korea’s Anti-Sex Trade Law.

Recently, I had to observe how the majority of members of the Northern Ireland Assembly blatantly disregarded scientific evidence (as well as sex workers’ testimony) against Clause 6 of Lord Morrow’s Human Trafficking and Exploitation Bill. As you will well be aware, MLAs voted to criminalise the purchase of sexual services a mere three days after the Department of Justice published its first-ever comprehensive research report into prostitution in Northern Ireland, conducted by senior colleagues at Queen’s University. As your colleague, Justice Minister David Ford, stated, he saw no evidence to suggest that criminalising the purchase of sexual services would reduce the incidence of trafficking. However, he added that “the report contains evidence to suggest that criminalising the purchasing of sex … may create further risk and hardship for those individuals, particularly women involved in prostitution.”

Earlier this year, the EU adopted a report by Mary Honeyball, MEP, as a resolution to endorse criminalising the purchase of sexual services in EU countries, despite evidence provided to counter her claims signed by numerous experts in the field and a statement by hundreds of organisations. Regardless of one’s personal opinion on the matter, Ms Honeyball’s report was deeply flawed by any standards, and I must ask you: how is it that a sound research report as the one by the researchers at Queen’s can be dismissed so easily while a clearly biased report such as Ms Honeyball’s can be adopted as a EU resolution? The answer is simple: it just isn’t very easy for politicians such as yourselves to vote against human trafficking bills or bills to criminalise sex workers’ clients, because you must certainly be worried that the public might perceive it as promoting either a crime – human trafficking – or what some people may still consider as immoral – selling and buying sexual services.

Although I have submitted evidence to Rhoda Grant’s consultation in Scotland and, much the same, to Lord Morrow’s consultation in Northern Ireland, which you are certainly invited to explore, I would like to ask you to first look at the detailed evidence submitted by the English Collective of Prostitutes, titled Briefing against clauses to the Modern Slavery Bill to prohibit the purchase of sexual services.

Key points include:

- Support for the amendment which would remove the offence of loitering and soliciting for sex workers

- Strong opposition to the clauses criminalising clients, on the basis of sex workers’ safety

- Evidence to counter the claim that the Swedish anti-prostitution law has allegedly resulted in a reduction of human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation or a reduction of prostitution

- Evidence that the treatment of sex workers in Sweden has worsened since the adoption of the Swedish Model

- The fact that once again, like in Northern Ireland, the evidence submitted by sex workers is being ignored

You do not have to agree with people’s choices to sell or buy sexual services, but you need to accept these choices and must refrain from introducing laws that endanger people selling sex, even more so if there is no sufficient evidence that the measure would yield any success with regards to the declared aim to reduce human trafficking.

I therefore ask you to be show courage and represent sex workers in the same way you represent your other constituents. If you really want to protect sex workers, don’t give in to misguided bill proposals based on morality. As Justice Minister David Ford pointed out ahead of the vote in the assembly: “It’s not about morals. It’s about how to best address the issues.”

Best Regards,

Matthias Lehmann

ps. My native Germany has taken a different approach to prostitution legislation, which is frequently misrepresented in the media and by anti-prostitution activists. Therefore, I would like to point you at a short article of mine looking at the Lies & Truths about the German Prostitution Act – An Introduction for the Uninitiated.

+++ UPDATE: The amendment to the Modern Slavery Bill put forward by Fiona Mactaggart MP, which would have criminalised sex workers’ clients, was dropped without even going to a vote. Another amendment put forward by Yvette Cooper MP, Shadow Home Secretary, calling for a “review of the links between prostitution and human trafficking and sexual exploitation”, which was put forward as an alternative to Fiona Mactaggart’s, was defeated by 283 votes to 229. Please listen to the excellent speech by John McDonnell MP. Alternatively you can view the video or read the full transcript included in a statement by the English Collective of Prostitutes. +++

MOGEF launches campaign to eradicate prostitution

The following text is a summary of an article on the official website of the Seoul Metropolitan Government. This post does in no way represent an endorsement of the campaign outlined therein, but is solely provided to illustrate the South Korean government’s continued refusal to acknowledge the rights of sex workers and the self-referential pat on its back for continuing to criminalise sex work, despite growing calls to decriminalise it, including from UN General Secretary Ban Ki Moon.

On September 16th, South Korea’s Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF) launched a campaign in Seoul to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the adoption of the Anti-Sex Trade Laws. The campaign will be implemented nationwide “to build a healthy society by eradicating prostitution”

The ministry launched the campaign at Seoul’s City Hall in attendance of Kim Hee Jung, minister of MOGEF, and Kang Weol Gu, head of the Women’s Human Rights Commission of Korea (WHRCK). The event was hosted by the Women’s Human Rights Commission of Korea and the Dasi Hamkke Center*, and lasted for two and half hours. The participants distributed brochures and delivered messages to eradicate prostitution. Posters displayed the achievements of the activities to eradicate prostitution and protect victims over the last 10 years.

The ministry launched the campaign at Seoul’s City Hall in attendance of Kim Hee Jung, minister of MOGEF, and Kang Weol Gu, head of the Women’s Human Rights Commission of Korea (WHRCK). The event was hosted by the Women’s Human Rights Commission of Korea and the Dasi Hamkke Center*, and lasted for two and half hours. The participants distributed brochures and delivered messages to eradicate prostitution. Posters displayed the achievements of the activities to eradicate prostitution and protect victims over the last 10 years.

MOGEF will continue its campaign under the theme “sex cannot be bought and sold” in 16 cities all over South Korea. The campaign will also be joined by the US Embassy in Korea, the US Forces in Korea, and the Cambodian Government.

Minister Kim Hee Jung stated that “prostitution must be eradicated as it violates human dignity. Hence, measures to punish those involved in prostitution should be strongly enforced. People must understand that human beings cannot be traded like commodities.” MOGEF, in cooperation with other institutions, will continue the campaign using TV and other media to raise public awareness of the sexual exploitation of women and children, the minister added.

The slogan on the above poster above reads “There’s something that’s not tradable in this world.”

*The Dasi Hamkke Center is a non-governmental and governmental collaboration agency offering exit programmes and counselling for “victims of sex trafficking and women in prostitution”. The centre is administered by Hansorihoe (United Voice), an umbrella organisation of anti-prostitution NGOs that frequently collaborate with MOGEF.

Sex, Lies, and Abolitionists

How prostitution abolitionists defame sex workers’ rights activists

The following comment was left on my blog last night.

Are you actually interested in the suffering of women who were forced into prostitution and who are hard up? If yes, you could read the following: Your Justifications are Killing Us

– Sophie

Rather than replying in the comment section only, I chose to respond more publicly in this post, to highlight the defamation that proponents of sex workers’ rights frequently have to endure.

Dear Sophie,

I do indeed take an interest in forced prostitution, though without your apparent limitation to women. I already knew the text you sent me. Even though I do not wish to deny the personal experiences of the author, I do take issue with the message she aims to convey with her text as well as with the blatant lies she spreads. In the following, I will respond to selected paragraphs of her post and thus, to your comment.

“Too much of the Left is made of male-thought, and in this thinking it not surprising that the Left has always justify the sex trade, and ignore the reality of life for the prostituted.” – Rebecca Mott

To give but one example to challenge her view, I shall name the German prostitution law (ProstG), which was an initiative by the female members of the German Green Party who by no means ignored the reality of sex workers. The ProstG abolished the statutory offence of the „promotion of prostitution” and made it possible to create better working conditions for sex workers without rendering oneself liable to prosecution.

Since the author mentions her view about which groups dominate the prostitution discourse, how about we take a look at the spectrum of prostitution abolitionists? In my view, those are predominantly radical feminists or members of faith-based organisations.

They are the ones who ignore the realities of sex workers, since their opinions often rest on their own concepts of morality and disproven research. I have no problem with anyone who doesn’t consider sex work as a desirable occupation or wishes to write about it and try to have others think about it, too. That falls under freedom of expression. That, however, is not what prostitution abolitionists are content with.

“If you scream and shout that you’re not a victim you are suffering from a false consciousness. And if you try to convince them that you’re not even suffering from a false consciousness, they will say: ‘Well you’re not representative'”.

“If you scream and shout that you’re not a victim you are suffering from a false consciousness. And if you try to convince them that you’re not even suffering from a false consciousness, they will say: ‘Well you’re not representative'”.

– Pye Jacobsson, Swedish sex worker and activist URL

The term „prostituted“ supports the notion that sex workers lack agency and aren’t able to make informed decisions. “to be prostituted” is a passive term that supports the notion that one cannot actively choose to work as sex worker. Is a construction worker “constructed” then?

“I am tired of everyone letting the left off the hook – I tired of waiting for the Left to get on board with abolition – I tired of men who Leftist making their porn stash and their consumption of the prostituted is somehow better than right-wing men who do exactly the same.” – Rebecca Mott

I, on the other hand, am tired that forced prostitution and pornography are conflated time and again, and that those who oppose the criminalisation of sex work are branded as proponents of sexual exploitation.

“In this post, I will speak of the many leftist cliches that have said to me, or I have read, or had fed to me by the media.” – Rebecca Mott

I don’t know which media the author refers to here, but I cannot support her view that the media are currently engaged in a campaign for the rights of sex workers. Rather, prostitution abolitionists frequently dominate the discourse and silence any dissenters. (See my previous post about a German talk show in featuring prominent prostitution abolitionist Alice Schwarzer) URL

The following statement is a typical example for that.

“Much of the poison-speech by the Left is the language of pimps and punters – men who are not pimps and punters parrots their words without questioning. I was consumed by many Leftist punters who justify all their tortures – I had profiteers selling me who imagine they were on the Left, hell they were sexual outlaws, they were empowering women, they were model-day freedom fighters.” – Rebecca Mott

If you don’t agree with them, prostitution abolitionists will denounce you as pimp, punter, torturer or – here – will-less parrot.

“I write to the Left, for my heart is exploring with pain and grief – silence round the Left betraying the prostituted class is killing the prostituted every day.” – Rebecca Mott

Again, the author conveys that the left ignored the reality. I would like to know whom she is talking about, but that she fails to elaborate on. I suppose that according to current criteria, you can call me leftist, and where I am concerned, I did seek the dialogue with prostitution abolitionists several times, only to be faced with attempts to defame me, distort my views into the opposite, or shout me down.

“The major one is that if you unionise the sex trade, then it will be fine and dandy. I agree with unions for workers – but there we the major flaw – being embedded in the sex trade is not work, the prostituted class are not workers. They are in the conditions of slavery, of having their human rights stripped from them – they are not workers. To frame it as work, where all that need to be done putting in basic health and safety regulations, all that need to be done is to get a shop steward who go to the sex trade profiteer and speak of working rights for the prostituted. Think a little, and you will see this is nonsense.” – Rebecca Mott

Sex worker unions are indeed no cure-all. However, the notion that sustainable improvements could be achieved without them is a misconception. The interests of sex workers are best represented by sex workers themselves. Those include fighting forced prostitution and violence, by the way. But for as long as prostitution abolitionists fight against sex work itself, a collaboration with sex workers is hardly in the cards. Sex work is work. Forced prostitution is forced sexual labour.

“When there are unions for the prostituted – they always are dominated by the profiteers, punters and those who support painting the myth that the sex trade is safe.” – Rebecca Mott

That is a blatant lie. Information about sex worker organisations can be easily obtained. I recommend the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) as a starting point.

“Unions that exist do not include the prostitute who is trapped in a brothel, do not include women in the porn that is daily torture, do not include the under-aged prostitute trapped in a room with lines of men consuming her.” – Rebecca Mott

While it is true that those forced into prostitution usually have no access to sex worker organisations, it is also true that forced prostitutes represent the minority of sex workers. So what is the answer? To defame sex workers, who like any other working person work on their own accord, and defame their organisations, including the services and assistance they offer? Among others, those include assistance to exit sex work, counselling (e.g. when suffering from sex worker burnout), or the opportunity to report suspected cases of forced prostitution. Does doing away with those sound like a good plan?

“No, unions are not for the ordinary and average woman or girl – for those unions have no intention to stop the routine rapes, the routine beating ups, the routine throwing away of the prostituted. No, the purpose of these unions is to whitewash away all the normal male hate and violence that underpins all aspects of the sex trade.” – Rebecca Mott

See above. One can easily learn about the objectives of sex worker organisations. The supposed “intentions” that the author describes are brazen defamations.

“Do not back any sex trade union – they do not give a damn about the prostituted, they care about pimps and punters.” – Rebecca Mott

This statement demonstrates that the author is not in the least interested in the rights of sex workers.

“It is a union run and controlled by managers, but more by managers who view the prostituted as goods and never as humans. Your belief in unions is killing the prostituted every day.” – Rebecca Mott

The author fails again to disclose what union(s) she is talking about. Her statement is a general condemnation of all sex worker organisations that aims to defame their members and work. Therefore, I will not respond to all further paragraphs, but only to a few additional points.

Sex workers protest against police crackdowns in Seoul [Photo: AP/Lee Jin-man]

“I would see punters who had brutalise me and other prostitutes on marches, in meetings or part of liberal religions – fighting with all the might for rights and dignity of all humans.” – Rebecca Mott

I heard people raise suspicions that sex workers in South Korea were forced to participate in demonstrations. I discussed this with Korean sex workers who I suppose the author would claim belong to this “leftist riff-raff”. None of them was able to confirm this suspicion.

“That when I learnt the lesson I have never lost – these men did not fight for the dignity and rights of the prostituted foe we were not and cannot be classed as humans – we were just goods for them to use to consume and throw away.” – Rebecca Mott

I believe that the information that I published on this blog and via Facebook speak for themselves and refute the author’s portrayal of “these men” as a homogeneous group.

“We were not given access to human rights” – Rebecca Mott

Here I agree. The rights of sex workers are indeed frequently violated and only unagitated discussions about possible countermeasures will lead to a sustainable reduction of such violations. Not only should sex worker participate in these discussions – they should be the protagonists in them.

“Please question your Leftist views if they discard the prostituted class.” – Rebecca Mott

Please question your views if they undermine the rights of sex workers. Failing to safeguard sex workers’ rights, will prevent fighting forced prostitution and violence in sex work effectively.

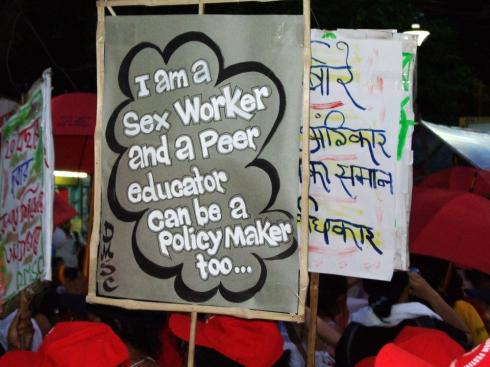

Sex Workers’ Freedom Rally in Kolkata, India [Photo by Matt Lemon Photography]

![2015 08 09 Kaera Wolf @Isis7wolf quit quite “sexist propaganda” [1]](https://researchprojectkorea.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/2015-08-09-kaera-wolf-isis7wolf-quit-quite-e2809csexist-propagandae2809d-1.jpg?w=500&h=175)