“I feel used” – Behind the scenes of Groove Korea’s cover story

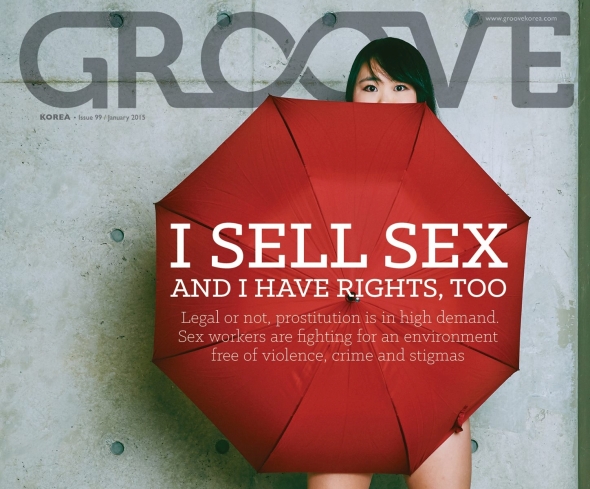

Cover photo of Groove Korea’s January Issue © Groove Korea Magazine 2014. All Rights Reserved.

Summary

The January issue of Groove Korea, an English language magazine published in Seoul, featured an editorial and a cover story about the fight of sex workers for the decriminalisation of sex work in South Korea. Although overall, it is one of the better articles on the subject, it left a bitter taste in the mouths of the sex workers interviewed for the piece, as well as mine. Coming in the immediate aftermath of the negative experience with the Wall Street Journal, it left me wondering if journalistic ethics is in fact a contradiction in itself. The description of what happened behind the scenes is not intended as a hatchet job or to publicly cry over spilled milk but to illustrate which problems occurred and why, and how journalists could avoid misrepresenting and offending the very people who provide them with information for their articles.

“Every human deserves safety”

Sex workers defend their labor, health and civil rights

Editorial By Yeoni Kim, sex worker and activist

Please click here to view it as PDF (with kind permission from Groove Korea)

Alternatively, you can read it here.

“I sell sex and I have rights, too”

Sex workers fight for a work environment that’s safe, decriminalized and free of trafficking

Article by Anita McKay, journalist

Edited by Elaine Ramirez, Editorial Director

Please click here to view it as PDF (with kind permission from Groove Korea).

Alternatively, you can read it here.

Preface

While I usually refrain from using the personal pronoun “we” when writing about matters that concern sex workers, on this occasion, Yeoni Kim, Lucien Lee and myself were all interviewed for the article in question and thus jointly affected by the treatment we received from Groove Korea. Although we criticise the latter, we do appreciate that by inviting Yeoni Kim to write the editorial and by featuring Anita McKay’s article as cover story, Groove Korea has directed much-needed attention to the struggle of sex workers in South Korea to have their rights respected and voices heard. However, we feel that on several occasions, we were treated unfairly and disrespectfully, both of which could and should have been avoided, especially in light of the lengthy run-up to the publication and the great amount of time invested by us.

Main grievances

Firstly, none of us were informed that the photographer for the photo shoot was not from Groove Korea but hired externally, with implications that will be outlined below. Secondly, we were given an extremely short time span in which to check the draft of Anita McKay’s article, which contained numerous problematic passages. Thirdly, the layout added an unnecessary sensationalising overtone to the article. (Please download the PDF above to view the article as it appeared in the print issue.) We also found the problem management of Groove Korea’s staff inadequate, and finally, a message by the editor, posted publicly on Facebook, grossly disrespectful.

Photo shoot

Due to the stigma attached to sex work, it goes without saying that sex workers are not always comfortable to appear in the media, which is why they often use masks to hide part of all of their faces. Since Anita McKay appeared (and was made) well aware of the sensitivity of the subject matter of her article, it remains a mystery to us how Groove Korea could not consider it important to inform us that they would not use an in-house photographer. The fact that they hired someone externally caused two problems.

Firstly, it had been agreed that apart from taking photos to be used for the article, the photographer would also take photos, which could then be used for a video project by Voice4Sexworkers, scheduled to be published on December 17th, the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers. Although the photos were taken, Ms Kim and Ms Lee were later informed that they could only use them if they would purchase them from the photographer, who, as they then learnt, was hired externally.

Needless to say that they had gladly taken time out of their days to meet Ms McKay for the interviews, and meet a second time for the photo shoot, and we certainly all appreciate that Ms Kim was invited to write the editorial. However, asking them to pay for the photos, which we had actually considered a nice gesture in return for the time spent, was less than discourteous. Not enough with that, we were also given the runaround in trying to obtain this information, as nobody from Groove Korea tried to address this issue proactively.

The more serious problem stems from the fact that said photographer now has a number of photos of Ms Kim and Ms Lee in his possession, and since the communication went as dissatisfactory as it did, there is no way of knowing if the files are stored securely or if they were destroyed to avoid their accidental dissemination.

Recommendation: When interviewing sex workers, journalists should be forthcoming in informing them who will be present during interviews or photo shoots, and any sensitive files should not be held by external third parties. If so, however, it is the responsibility of the journalists in question to ensure that they are stored securely or destroyed afterwards.

Proofreading (Part I)

Journalists frequently blame inaccuracies and other problems in their articles on time constraints due to tight deadlines. While Ms McKay did her best to accommodate the schedules of Ms Kim and Ms Lee, it was agreed from the onset that we would be permitted to review the entire article prior to publication. When I checked my emails on the last Sunday before Christmas, I found that Ms McKay had sent the draft at 5am that morning, requesting our feedback by “5pm Sunday”. Although I started reviewing the article immediately, I only managed to find out by noon if she in fact meant “5pm today” – and she did.

Anita McKay had first contacted me at the end of May 2014, and between then and December, we had exchanged nearly 70 long and short emails, had a Skype interview for over two hours, and engaged in chats filling over ten pages. Ms Kim and Ms Lee, on their part, had also spent several hours responding to her questions in writing, and met her for an interview and for the photo shoot.

Regardless of Ms Kim and Ms Lee’s command of the English language, it is simply an audacity to send the draft during the small hours and expecting feedback a mere twelve hours later, when it was previously agreed that we would be given time to review it. In addition, the article was only sent to Ms Kim and myself, although by comparison, Ms Lee has the superior command of the English language necessary to review an article of that length, which Ms McKay would have been well aware of, having met both of them. The only explanation we received was that Ms Lee had never requested to receive the article prior to publication. As I stated previously, writing about sex work requires going the extra mile to avoid misrepresentations that may negatively affect public opinion and subsequently policy makers. In our view, Ms McKay gave up after a few hundred yards.

Proofreading (Part II)

The following examples from the draft are not intended to discredit Ms McKay but to illustrate how necessary thorough reviews are and how easily errors can occur, even if journalists might have the best intentions, which Ms McKay definitely had.

1. Kim admits that her story isn’t representative of a typical sex worker.

Lucien Lee responded that, “even though it is correct that Yeoni is not representative, since nobody is, saying that she is not a representative sex worker takes away credibility from her story.” The idea that there is some ‘representative’ sex worker experience is widely criticised by sex workers and others as the experiences of sex workers are extremely diverse. To Ms McKay’s credit, the sentence was changed and then properly reflected what Ms Kim had expressed: “Kim admits that not all sex workers had the choices that she did to enter the industry. While she took the job for the economic stability and flexibility it can offer, others had few alternatives.”

2. When sex workers are victimized by violence, they are treated as suspects. Society doesn’t think of us as victims of a crime.

Ms Lee explained that “Yeoni did say that but the translator stopped her from talking and then she translated parts of sentences to [Ms McKay]. The context should have been that “criminalization and social stigma often lead to violence towards sex workers but it’s difficult to report it. Even if a report is made, we become the suspects.” While the published version of the article no longer highlighted the above quote in a larger font, the actual quote remained unchanged, i.e. without the addition of the necessary context. Since the article mentions that some believe sex work per se to represent violence against women, it is disappointing that Ms McKay did not acknowledge the need to change this passage to better reflect Ms Kim’s statement.

3. But to those who join the sex industry by choice, the real danger stems largely from laws that put all forms of sex work, including trafficking, under one umbrella.

When I first saw this sentence, I stared at it in disbelief. At no point had anyone suggested that ‘trafficking’ was a form of sex work. To the contrary. When Ms McKay sent additional questions to me in December, my responses included detailed information about the harms caused by the conflation of sex work and human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation. To see this in a final draft simply made me speechless.

As I learnt later, however, the sentence had not appeared in Ms McKay’s original draft but was inserted during the editing process, for which Elaine Ramirez was responsible, Groove Korea’s editorial director. Again to Ms McKay’s credit, the sentence was later removed, but it serves as a striking example of how editors, who in most cases will be less familiar with a given subject than the author who did the actual research, can obscure or misrepresent crucial information.

4. By fusing sex work with sex trafficking, [Matthias Lehmann] says, they are refusing to recognize sex work as work.

The term ‘sex trafficking’ originally appeared nine times in Ms McKay’s article, although I had explained in great detail, both in writing and during our interview, why I reject the term and instead always use the admittedly long-winded moniker ‘human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation’. Using it anyway was certainly Ms McKay’s prerogative, but I frankly do not understand why she chose to ignore my concerns. Putting the very term in my mouth, however, goes beyond mere negligence, and in addition, she also used the term when she cited the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW). When I contacted a colleague there to verify my belief that the term never appeared in any of the organisation’s publications, she sent me the following passage, which I subsequently forwarded to Ms McKay. It summarises my own objections perfectly.

“Some GAATW members and allies have also made a deliberate choice not to use the term ‘sex trafficking’ based on concerns that all human rights violations against trafficked persons across all occupational sectors should be addressed, not just the sexual aspects of trafficked persons’ experiences. There is also a worry that the term “sex trafficking’ encourages voyeurism by directing public attention to the sensationalistic aspects of what women were forced to do rather than the full range of human rights violations women experienced and the human rights protections they are entitled to. A sole focus on trafficking for the purposes of prostitution can also divert attention and urgently needed resources from human rights violations in other sectors, e.g. labour exploitation or the ‘trafficking-like’ effects of particular government overseas labour programs.” – Excerpt from the GAATW Working Paper “Exploring Links between Trafficking and Gender” by Julie Ham. See also “Hey, mind your language” by Borislav Gerasimov.

While Ms McKay eventually modified her article, she included the term once because, as she explained, it was a direct quote from a government website. What’s curious about that is that direct quotes are usually put in quotation marks, while paraphrased passages are not. But while she didn’t add quotation marks here, she added them in a passage where she paraphrased a statement by Yeoni Kim about “physical and emotional” services in exchange for money. I had pointed out to Ms McKay that adding quotation marks only to those three words actually added an air of scepticism, rather than indicating it as a quote, but it remained unchanged.

There were other problems in the draft, such as the definition of sex work as “any exchange of sex services for material compensation, whether voluntary or involuntary” – involuntary sex is rape, and thankfully, the passage was later changed – or the inclusion of the contentious US Trafficking in Persons Report, but there simple wasn’t enough time to address all of them. To her credit, Ms McKay corrected quite a few passages, but others she ignored. It is frustrating that after all the time invested by everyone involved, the final article still contains problematic passages, which could have easily been avoided.

Recommendation: Writing about sex work does require going the extra mile to avoid misrepresentations that may negatively affect public opinion and subsequently policy makers. Therefore, if sex workers or others grant interviews, journalists should allow sufficient time to discuss their drafts with them to ensure they appropriately relayed the information provided to them.

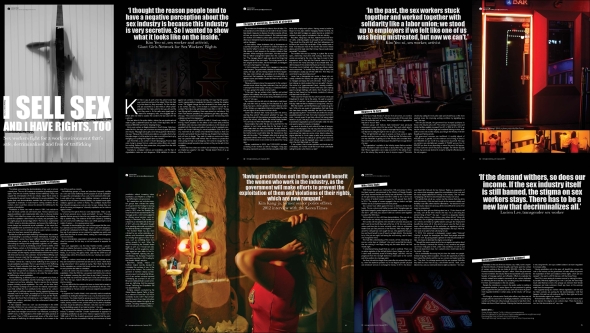

Layout

In addition to the problems detailed above, I was taken aback by the dark, and in my view, sensationalising layout of the article, which is why I discussed it with a colleague who is both a sex worker activist and a web designer. She commented,

“The layout makes the article look like an obituary, especially the first black-rimmed page and those pages that only feature text. It seems to paint a picture of sex work as a pit of eternal darkness from which there is no escape. Any graphic designer worth her or his salt knows which colour creates what kind of mood. There’s a reason why dramatic movies, for example, use big white letters on dark backgrounds – just as this articles does.”

I asked Ms McKay why such a dark colour scheme had been chosen, also pointing out that in the past, articles about South Korea’s LGBT community, for example, had not been featured in such a manner. Ms McKay didn’t answer my question but replied that she had requested for the layout to be altered. She was told, however, that it was too late for any changes, to which my colleague responded,

“That’s nothing. A graphic designer does that in a few minutes.”

The black layout remained, but changes were in fact made. My request to add a description to Yeoni Kim’s photo series ‘Working? Working!’ was accommodated, but interestingly, the highlighted quotes in the article were changed, too. As mentioned above, the quote by Yeoni Kim that lacked the proper context remained unchanged, but at least it was no longer emphasised. In addition, Lucien Lee’s quote was exchanged for another.

![Quote of Lucien Lee [Draft version]](https://researchprojectkorea.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/quote-of-lucien-lee-draft-version.jpg?w=590&h=263) Draft Version

Draft Version

![Quote of Lucien Lee [Published version]](https://researchprojectkorea.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/quote-of-lucien-lee-published-version.jpg?w=590&h=271) Published Version

Published Version

In both quotes Ms Lee calls for the decriminalisation of sex work but in the previously used one, she emphasised that the decriminalisation should extend to sex workers’ business partners and clients. This difference is important, as politicians and anti-prostitution activists continue to claim that the Swedish Model somehow ‘decriminalises’ sex workers. Exchanging the quote seems suspicious, but even if it were purely coincidental, questions remain why it was changed and why we were told that changes to the layout could no longer be made.

![Quote of Matthias Lehmann [Draft version]](https://researchprojectkorea.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/quote-of-matthias-lehmann-draft-version.jpg?w=590&h=232) Draft Version

Draft Version

My own quote, previously featured prominently in the draft, was no longer highlighted in the published version. Frankly, I do not need to see my name in the papers, but I couldn’t help but wonder why the message was suddenly no longer considered noteworthy. Honi soit qui mal y pense – shamed be he who thinks ill of it.

It’s interesting, however, that on the same page, featuring a photo of Yeoni Kim, later a statement by Kang Ja Kim was highlighted. Kang Ja Kim is a former senior police officer who played a key role in the creation of the Anti-Sex Trade Laws and in abolishing red-light districts. While it is important to note that she has in the meantime spoken out in favour of allowing brothels to operate in designated areas, she remains a proponent of doing so only in limited areas and under strict regulations, which research has shown does not benefit the rights of sex workers.

“Licensing or registration of the sex industry has been of limited benefit in terms of public health and human rights outcomes for sex workers. … Licensing or registration systems are usually accompanied by criminal penalties for sex industry businesses and individual sex workers who operate outside of the legal framework. Licensing or registration models may provide some health benefits to the small part of the sex industry that is regulated, but do not improve health outcomes for the broader population of sex workers.” – Excerpt from “Sex Work and the Law in Asia and the Pacific” by UNDP

And while it’s commendable that Kang Ja Kim at least acknowledges now that a different legal approach is necessary, the reasons for her shift in opinion misrepresent the diversity of sex workers’ clients, who, in her view, are “the disabled, illegal immigrants and widowers” as well as “men who are incapable of controlling their [sex] drives”. It certainly would have been more appropriate to feature a quote from Yeoni Kim together with the photo of her than one of a former “anti-prostitution crusader”.

Recommendation: Regardless of how good the content of any given article may be, a poorly chosen title, layout, or image can easily diminish its value. More often than not, journalists have no say in these matters. Editors should ensure that their choices do not undermine the voices of sex workers, who should be given the opportunity to review not only the content but also the layout of articles they were interviewed for.

Conclusion: Journalistic ethics – A contradiction in itself?

“I have no obligation to send a copy of the article to the sources before it gets published. In fact, it’s against the policy of many news organisations.” – Statement by a journalist

Writing about sex work certainly is a minefield and making everybody happy is a difficult task to accomplish for both journalists and academic researchers. However, if the above statement a journalist once made in an email to me is anything to go by, then one must wonder why journalists think their sources should oblige their interview requests. Time constraints and a lack of influence over the layout are one thing, but misrepresentations that can negatively affect and offend the very people they interview is another.

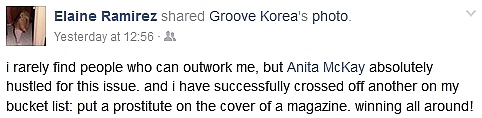

As I wrote to Anita McKay, one should certainly not mistake journalists for minute takers who will merely document verbatim what was said in their presence or expect journalistic articles to be advocacy pieces. But the fact that Anita McKay’s article is overall one of the better ones still doesn’t mean that the end justified the means. And it certainly didn’t justify this status update by Groove Korea’s editorial director Elaine Ramirez.

Facebook post by Groove Korea’s editorial director Elaine Ramirez

Note that Ms Ramirez didn’t celebrate that she had managed to prominently feature a story about sex worker’s rights but that she “put a prostitute on the cover of a magazine”. As illustrated above, Ms Ramirez doesn’t appear to pay much attention to using appropriate terms, or else she would have been aware that – both in English and Korean – Yeoni Kim always refers to herself as ‘sex worker’, rather than using the stigma-laden term ‘prostitute’.

“The term ‘prostitute’ does not simply mean a person who sells her or his sexual labour (although rarely used to describe men in sex work), but brings with it layers of ‘knowledge’ about her worth, drug status, childhood, integrity, personal hygiene and sexual health. When the media refers to a woman as a prostitute, or when such a story remains on the news cycle for only a day, it is not done in isolation, but in the context of this complex history.” – Excerpt from “Dehumanising sex workers: what’s ‘prostitute’ got to do with it?” by Lizzie Smith, Research Officer at La Trobe University. See also “The P-Word: A 101” by Caty Simon

Upon seeing Ms Ramirez status update, Yeoni Kim wrote to me:

“That sentence makes me feel used by her and as if I am some second class citizen, not worthy of the same respect as other human beings.”

Yeoni Kim thus summed up the root problem of most media reports about sex work. As long as journalists refuse to treat sex workers with the respect they deserve, they frankly do not deserve to be given the time of day.

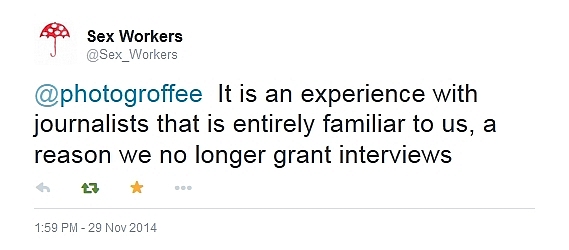

Tweet by the Philippine Sex Workers Collective

Epilogue

In light of the avalanche of sensationalising media reports that spread myths about sex work as well as human trafficking, I consider it very necessary for sex workers and researchers to engage with journalists in order to refute these frequent misrepresentations. It is impossible to do so all the time, since it is both unpaid and tiring, but over the last year, I invested a great deal of time in assisting journalists with their research. Looking back, I cannot help but to feel that it wasn’t worth it.

In my view, the fundamental difference between journalists and researchers who write about sex work is that researchers have a vested interest in establishing a trusting relationship with sex workers for the long term, while journalists can (and do) simply move on to the next story and worry less about that.

Whenever I write media critiques or leave comments on journalistic articles, some people respond by accusing me of being vindictive or trying to promote myself. These people never know, however, what happened behind the scenes, which is why I choose to illustrate that from time to time. Addressed to anyone feeling the need to question my motives for writing the above, I’ll just say: let’s see how you will like it when, after investing countless hours of unpaid work, you see facts misrepresented, words twisted, and people you care about as well as yourself treated with disrespect.

When dealing with journalists and photographers, get it in writing, tape record the conversations (and if they don’t want the conversation recorded, don’t continue to speak with them), get an attorney (perhaps a client) to review said ‘contract’ before you permit any photography. I learned these lessons the hard way. Unfortunately we all have to learn the lessons over and over again.

No matter how friendly the journalist sounds, or how chummy they want to get, they have their own agenda and it usually does not coincide with ours.

January 17, 2015 at 5:03 am

Oh god. Groove. If it makes you feel better I own a business in Korea and have been interviewed by Groove, 10 Magazine, and even some foreign outlets. All of them have been equally horrible. Even some very recognizable industry names have completely sensationalized small aspects of our interviews and then left out things I thought were absolute bombshells if you knew my industry.

So you can tell the ladies in the story that it’s not just sex work. Journalism these days is absolute garbage 80% of the time. Only do an interview after you’ve read that journalists work and are sure they will do a good, thorough job. Consider anyone else an utter joke.

January 22, 2015 at 9:05 am

Thanks for your comment. I wouldn’t call the folks at Groove horrible. As I said, the final article still is one of the better ones and it is good that they made it a cover story and asked Yeoni Kim write the editorial. But yes, checking what journalists have written in the past is always a must. I guess on this occasion, I had a better overall impression of the publication, but sadly, you are not the first one who has told me since that he’s not surprised about what happened.

January 22, 2015 at 1:02 pm

Pingback: Important Fundraiser for GRACE PERIOD 유예연대 | Research Project Korea

Groove also did a poor job with my interview on street harassment. They misquoted me and they used my story in a weird way. I had a long dialog with Elaine about how to improve her work on what she called women’s issues. I am frustrated to see that month later, you got this treatment. Clearly they ignored my feedback and advice.

April 8, 2015 at 11:57 pm

Sadly, I am not surprised. I heard a similar story from someone else in Korea, too. It’s probably a tad harsh to say so, but from her Facebook post, I can only assume that one “women’s issue’ that Elaine appears to be interested in is her own brand.

Wait until you see GRACE PERIOD. It reflects reality, unlike all the media malarkey. I’ve been pondering for a while whether or not to respond to the recent VICE report (“South Korean Love Industry”), which was one of the most ridiculous reports I’ve ever seen, but I really got better things to do. It’s just a shame that they allowed this to be published, when otherwise, there has been some good collaboration between sex workers and VICE.

April 9, 2015 at 9:09 am